DIABETES is something other people get … Something you never imagine that one day could turn your life upside down. But diabetes can strike at any time, leaving people of all ages with life-long challenges and, in some, cases very serious health issues including amputations, heart problems and strokes.

DIABETES is something other people get … Something you never imagine that one day could turn your life upside down. But diabetes can strike at any time, leaving people of all ages with life-long challenges and, in some, cases very serious health issues including amputations, heart problems and strokes.

Type 1 diabetes is especially worrying. It’s caused when the body’s insulin-producing cells within the pancreas are mysteriously killed off by your own own immune system. Children and young people are especially vulnerable . . .

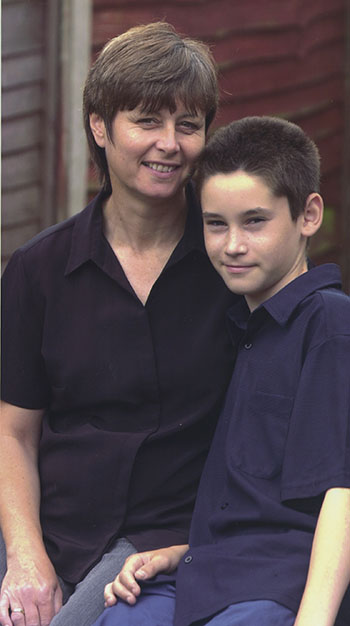

MUM’S STORY: Lynne Dowling

MUM’S STORY: Lynne Dowling

I FIRST suspected something was wrong (didn’t realise what) around the December before Joseph was diagnosed (March 9, 1994). He was three years-old.

I went to collect him from the playgroup Christmas party, and when I arrived, all the children were running around the village hall excitedly.

Everyone apart from Joseph who was sitting alone at the front not wanting to join in. He fell asleep on the way home.

I thought he must be coming down with something. But there was nothing I could put my finger on. He just didn’t seem right. I did take a water sample to the doctors, but it was given the “all clear.”

I spoke to the staff at his new nursery. They felt like I did — there was something not quite right, but what?

Then during one night in March of 94 Joseph kept getting up from his bed, going to the toilet and drinking water. He did this about 15 times before midnight. He was fine the next day, wanted to go to nursery, but I took another water sample to the doctors again.

This time the doctor said there was sugar in his water and I should go for him immediately so they could check his blood.

Our fears were confirmed, his blood sugar level was very high. We had to take him straight to hospital.

My 40-year-old cousin had type 1 diabetes from age 13 so I knew a limited amount about it. The first thing that hits you is how am I going to be able to give him two injections a day. I was devastated but knew it was going to be far worse for him.

I could not fault the treatment we received on that first day or any time since the paediatric diabetes team at the Countess of Chester hospital. They were brilliant and we can contact them any time for support if required.

When we first got home the worst thing was giving Joe his injections. It broke my heart — especially when I had to go into his bedroom and either inject him or stick a needle into his little fingers and carry out one of the many daily blood sugar tests.

At first I would have to grab him to me, hold on tight and inject into his little bottom. His soft cheeks would clench and I knew it was hurting him so much.

Before all this hapened his face always lit up whenever I came into his room. Now, whenever he heard me coming into his room he would cry and hide under the duvet.

Quite often I had to leave the room, so he couldn’t see me cry. It was extremely difficult to cope with all this.

I long for a cure for diabetes — I even feel guilty, that I am to blame in some way for his condition. I continually try to keep things in perspective and know that there are other, more serious diseases that children have to deal with, but I would love him to be able to lead a more carefree life — like lots of his playmates — without me nagging him every time he goes out about blood sugar, snacks, dextrose and meal times.

JOE’S STORY: Joe Dowling, aged 13, from Great Sutton, Wirral — attends Whitby High School, Ellesmere Port

JOE’S STORY: Joe Dowling, aged 13, from Great Sutton, Wirral — attends Whitby High School, Ellesmere Port

HAVING to give myself insulin injections twice a day — before breakfast and before tea — is the worst part. And I’ll probably soon have to do inject myself even more.

It took me until I was ten before I could do it myself, but I had to do it if I was to go with my friends on the school holiday. That made me do it.

“I spent lots of time practising injecting oranges — they didn’t moan as much as I did!

“I usually inject straight into my thighs. Sometimes it hurts more than others, and there are times when I just can’t bring myself to do it and have to ask mum.

“It’s important to keep changing the place where you inject, because otherwise the insulin won’t be as effective and I’ll end up with lumpy legs!

I also have to give myself loads of blood sugar tests which means pricking my fingers with needles and checking the sugar levels in my blood blood.

I have to do it every lunch hour at school, which can be a bit annoying because there always seems to be people coming to have a look at what I am doing!

A perfect reading is between 4 and 7, any lower then I’m in trouble and I have to eat something sugary pretty quickly. If I don’t I’ll start to feel really hungry, possibly pass out (hypoglycaemic attacks), and then if I still don’t get some sugar into my system I’ll have a fit.

Lately I am regularly going low. It’s something to do with my age — and the fact that I don’t eat too well.

I’ve had a couple of bad hypos this year — I even bit through the side of my tongue. I didn’t know anything about it, but mum says it was all a bit scary.

Mum says that people without diabetes rarely have blood sugar levels above 7, but I’ve often been as high as 20, so I guess this isn’t too good. I don’t eat very much, and don’t seem to have a good appetite, but one ice cream, or a chocolate bar is enough to send me sky high. Then I feel dead thirsty, drinking gallons of water.

I know peope with diabetes should not eat sugary things regularly, but one small treat now and again isn’t going to do too much harm.”

While his 11-year-old twin brothers Dan and Ben play for one of the local junior football teams, Joe’s attention is switched towards music, lighting and DJ-ing.

I like football, but I just don’t seem to have the same energy levels as the rest of the lads. I get tired too easily. I know it’s because I don’t eat enough, but I just can’t face too much food. It makes me sick thinking about it.

Instead, I love DJ-ing. I’ve got a pretty good system and I go with dad to the local gym once a week to practice. I’ve only had one gig so far — at my brothers’ football club presentation night, but I’m now ready to take on more bookings, and there’s a chance that I might get a slot doing the roller disco show at the local leisure centre.

The only problem seems to be that my blood sugar levels drop quite quickly. I think it’s because of all the energy I use carrying the equipment from the car into the gym, and all the excitement. But I’ll get around that one.

I’m going to have to make sure that I try and eat better before the session and to keep munching crisps while I’m playing. I just hope people will be able to understand me when I’ve got a mouthful of food, that’s all.

It would be fantastic if a cure came about, but I’m not thinking that far ahead. If it comes great, if not, I’ll just carry on as I am.

- DIABETES is one of the biggest health challenges facing the United Kingdom today.

- The impact of the condition on both individuals and the NHS is enormous.

- In many cases the costs are the result of heart disease, blindness, kidney failure, strokes and amputations which result from poorly controlled diabetes. Often they are preventable.

- People with diabetes live with the condition every day of their lives and must play an active part. They make decisions which can have a major impact on their long term health.

- These decisions can only be made effectively if people have all the facts and support.

- Today in the UK too many people with diabetes are living in the dark.

- Less than half of people with diabetes realise it can cause heart disease yet people with diabetes are up to five times more likely to have heart disease.

- Almost three in ten do not link diabetes and blindness despite diabetes being the leading cause of blindness in the working age population.

The reason why people are living in the dark is clear

Data reported at the Diabetes UK annual professional conference in March highlighted the fact that nearly six out of ten GP practices in one area do not run dedicated diabetes clinics and only 10 per cent had structured education programmes

- Many people report being told they have ‘mild’ or ‘slight’ diabetes – as many as half of people with Type 2 diabetes already have complications at the time of diagnosis

- 13 per cent of people receive no explanation of diabetes at the time of their diagnosis and one in five received no written information

Steve Morgan Foundation commits £3million towards finding a cure for type 1 diabetes